Burning out

What’s the opposite of burning out?

If burning out means exhausting myself with work, then I would understand the opposite to mean hopping joyously between two states: (a) being challenged beyond my current capacity, and (b) decoupling from that challenge. The opposite of a burn out is the act of balancing in this sense: Every measure of winding can be balanced out with some unwinding. Focus <-> Unfocus.

The ability to avoid burning out is one of the most useful skills I learned in graduate school. In my first month there, it was mid-summer 2013, and I recall that the prevailing sentiment I had was one of emptiness, which I loved. I had less than a handful of acquaintances, some of them would become my closest friends in the following years, and my main concern was how to maintain a minimal amount of responsibilities in my life. It was easy to shed responsibilities, since I had few hobbies and distractions to begin with. My social baggage and ambitions were small, additionally: I wasn’t trying to grow a family, nor was I looking to take on any new skill.

I wanted to occupy my days with merely those activities which could contribute to my success in graduate school.

I was narrowing down my scope.

During this period of calibration I was fortunate to meet some people who had more experience than me, who highlighted the need to think long-term and balance intense studies and work with a healthy dose of distractions. Their advice was suggesting a broadening of scope, whereas my instincts were guiding me to a narrowing of scope. By this time, fall had arrived and the semester had officially started. I remember with eery clarity a specific advice someone gave me. It was an analogy, and maybe that explains why I remember it so distinctly:

Graduate school is a marathon: It’s not a sprint: You gotta pace yourself, get hydrated regularly, watch over your overall condition. Listen to your body. The goal is to reach the end, no matter how slowly.

This advice did reach me. But I had not idea how to play the marathon game. I could play the semester game quite well, however. Semesters have breaks between them, periods of respite. Little did I know that graduate school has no need for semesters. There are indeed courses and seminars and they are packed neatly into semesters. But stacked on top of semesters there’s a more important category of responsibilities of graduate school: deadlines for submitting research articles.

Deadlines tend to overlap constantly, they have no natural breaks between them. Additionally, as a graduate student, semesters would blur into one another without a break in-between because I would need to wrap-up the ending of one semester (such as grading exams after the exam session), or prepare for the start of the following semester (prepare examination sessions, projects, and classes).

Besides the lack of segmentation (non-overlapping semester) that I was used to, there was another challenging part in graduate school: the event horizon of knowledge only keeps broadening. There is no limit, or portioning, to the amount of reading and understanding one can amass in graduate school. I experienced this to be particularly true in the first 2-3 years.

My first burn-out

The consequence of this situation is that I kept piling more and more mini-projects, kept investing more and more effort. The periods of intense activity were fortunately still punctuated by small pockets of fresh air, merely enough to keep me going. This was mostly due to my friends and family, who expected of me to dedicate some time to (simply) hanging out with them, and I could not say “no” for too long before I would cave in and quit the work zone.

I think I was able to work for almost three years in this way. In Spring 2016, I was slowly realizing that I was speeding in the desert highway on an empty tank – so to speak. I had an important deadline for a paper in that period. After I submitted the paper, I could not work anymore, I could only pretend to.

Leading up to the deadline, I think that was the most focused periods of work in graduate school, but also the most difficult. I wasn’t good at it, however, because I wasn’t working efficiently and I was still a novice. I felt very creative and engaged, yet the problem was that I started having very serious sleeping problems. I found it impossible to shut off my problem-solving mind. And so I was thinking day and night about the research topic I was working on, leaving no room for restful sleep. No sleep: no effectiveness.

That was when I became interested in mindfulness and meditation. My interest was not purely pragmatic: I wasn’t strictly looking to calm my thoughts, but additionally there was a spiritual element that the activity of meditation was offering me, to fill the void I had created in my life.

After the deadline, I recall attending a surf workshop that we were holding with my research group somewhere in Bretagne, and that was one of the most calm periods my brain has ever experienced. I was done with the deadline, and all that was left for me to do was to meditate and enjoy, do sports, sit in the sun, socialize.

After the fall

That first burn-out was a wound that took almost a year to heal. In some sense, I’m still recovering. But the fall brought a few lessons.

First, I learned that I can be deliberate about entering a state of mind where I am thoroughly engaged, in the flow. This was not the case prior to this burn-out experience. And it applies not only to work (as a special activity) but to anything. It seems to be possible to engage and tone down deliberate effort; I was never able to actually start it, but I could set myself up in the right conditions for it eventually to occur.

Second, the practice of meditation stayed with me. It is something I still find valuable today. I use it not for help sleeping, but for general wellbeing, learning to accept the world as it is necessary for it to be.

Third, as a more general observation, I think I get the value of the “marathon vs. sprint” advice. It’s still a mental model that eludes me at times, however. I think there is a place and time for sprinting, but the overall attitude I want to maintain is that of a marathon. Combining them is difficult but probably worthwhile.

One difficulty in understanding this mental model is that it often doesn’t look like life is even a marathon, like it has an end. Rather, it looks like no end is experienced as an end. For example: If we’re not aware of ourselves at the moment of our death, do we truly experience that end? And if we are never content with any ending (a degree, a project, a contest, a dinner, an actual marathon, an exercise session), which is true of most of us, do we truly experience any end? Not sure. Moreover, there seems to always be room to re-begin.

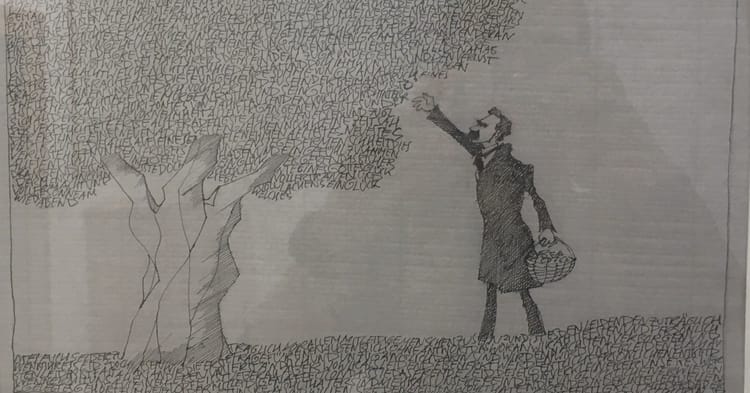

A year later, around late 2017, one more advice that echoes the same observation regarding marathons reached me from one of my closest friends in Lausanne. I did not have in sight the end of my PhD at that time yet. He had recently graduated and was cleaning up his whiteboard, clearing his office. This was around the time of his PhD graduation party, if I recall correctly, and was going to be the last time he erases his whiteboard before moving on with his life. There was an elephant doodle on the whiteboard which caught my attention as his hand was about to erase it, so I asked him what was that all about, intrigued not only by the artwork (somewhat crafty, but simple) but also by the foreign words (it was in Dutch). He explained the elephant was a symbolic representation of one of his favorite sayings, as follows:

“How do you eat an elephant?” the riddle goes. “One bite at a time.”

This friend, in particular, demonstrated to me that burning out is not necessary to perform at our best.

Comes the end

It is very appealing to persist in a state of challenging myself with tasks and objectives. I can see that happening in many colleagues and friends alike. It doesn’t even take a high-performing person to fall into that trap. Personally, I think it has to do with a complex combination of wanting to achieve much, focusing on growth, devaluing the importance of play and socializing, and underestimating long-term concerns.

Recently, I am more and more tempted to go one step further with the moral of the story of the marathon vs. sprint. I noticed that both a sprint and a marathon assume that there is an end in sight. In this view, projects are counted day-by-day and it's just the total span of time that changes: some activities are longer and require a sustained effort, others are shorter and benefit from bursts of action. What if we forego that assumption, however? So I’m toying with the image of a project as something more like a process instead of a journey, and that may reflect reality more faithfully, at least at times.

Comments ()