Essays are embers caught in time

I love writing. I love quite a few things, and writing is one of them. If I’ll ever find a way to write consistently, that would be my preferred way of earning a living and working meaningfully. One of the primary obstacles to doing that, however, is that I’m quite afraid of standing for something concrete, or committing to an opinion.

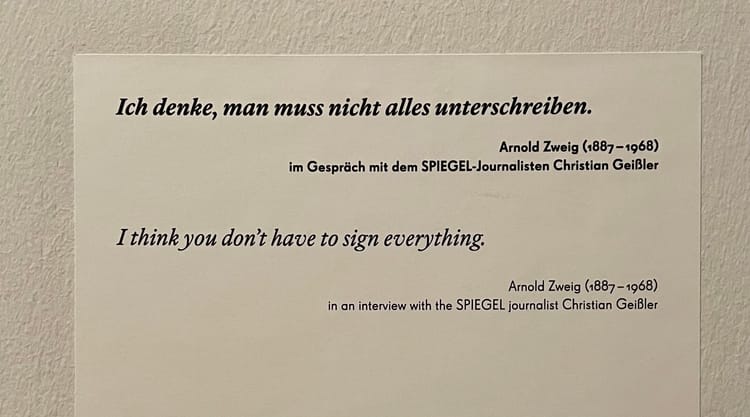

Writing has this quality of making my beliefs clearly articulated. Ideas, statements, biases, opinions, the facts seen through the prism of my reality, all seem to become set in stone as soon as I write them down. "Writing binds me irreversibly to certain beliefs." That’s a frightening thought when I put it that way. An eternal committment *shudders*. What if I gain an understanding that a prior opinion of mine is clearly wrong, or what if I change my mind?

Many people who enjoy writing but not doing it are likely, like me, self-censoring themselves. They avoid it out of fear, they put it off, or allow themselves to get easily distracted while trying to practice it. This is not strictly speaking a problem, depending on the person: Writing doesn’t truly feel like a priority for me, for instance, even though I just said I love it. I have other matters that call to me and they seem more urgent in comparison to writing.

The easy things are easier, they feel more urgent. The hard things feels like a mere indulgence, so it’s OK to postpone them, especially if the outcome of those activities feel eternal. Eternity can wait.

I’m not eternal. To the contrary, I see more and more clearly how unmerciful my perception of the passing of time is. Not only unmerciful, but this perception can be very misleading as well.

Does time pass faster as I age?

My perception of how time passes seems to have changed with my age. The younger Adi would see time go slowly. Days were ripe with specific happenings. The 32-year old Adi seems to think that time is less and less discrete, speeding up more and more. It’s not just my personal observation, I heard it from others and seen it discussed in books. It is said that people into their more mature years observe the passing of time at a faster pace compared to their younger years.

I suspect it is a self-fulfilling mindset to believe that the passing of time accelerates with age. What I believe is happening, instead of such an acceleration, is that we become more experienced, more acutely aware of the concept of time and the symptoms of age, and consequently become more attached to the significance of a day, a week, a year, an hour.

The first time I stared at a mountain peak all I could see was a huge ramp and a descent on the other side. After looking at a peak a thousand times, I will see thousands of details and nuances, I understand the many faces of the mountain peak because I have developed my eye for it. It’s the same with the passing of time: I get it now after more experiences gained over years, I detect its edges way better, the sharp contours reveal themselves easily to my naked eye. Do I need to focus on those tiny features? Maybe not, or at least not always. It’s in fact easy to avoid the mindset of details once I decide to do so, and regard the mountain of time as a whole.

The passing of time actually manifests as a relation between me and the world. It’s not a process that is purely controlled from the outside. Instead, my mind co-creates this perception as it comes in contact with reality, the gravitational field and the other beings around me. This is not much of a breakthrough. It’s quite intuitive, in fact: Since it’s my perception it's obvious I am part of that process. [1]

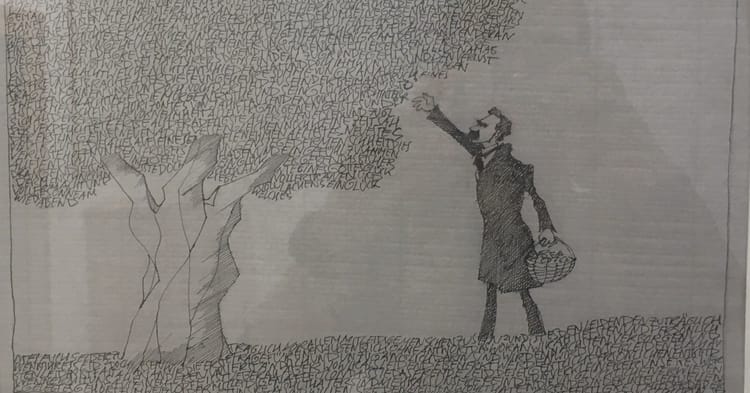

Reflecting on my relation with time in this manner can be quite fruitful, as it highlights some minimal amount of control resting in my hands. Put differently: part of my perception of how time passes is of my own creation. I can take this experiment to the next level, then: Observing reality this way leads me to understand that writing is inherently ephemeral. An essay becomes obsolete, in a sense, as soon as I lay down the words.

I live in time. I experience time and with the help of other senses I construct a model of the world on top of that experience. A piece of writing, in contrast, is one snapshot of that model, fundamentally caught in time. For this reason, an author is never bound to their writing for more than an instant. There is indeed a firm link between the author and the work, but it’s a causal one. The author caused the essay. The two are not bound permanently, because one continues living, while the other is an ember caught in time.

We can push beyond the written word. Even my thoughts are artefacts in time, of previous versions of myself, while my actual being continues living in time. This is actually common sense now that I think more of it.

Flakiness and flexibility

A thought on paper or online is a concrete stance on something. On many topics I change my mind all the time. We all do, thankfully. I'm not talking here about base beliefs, or eternal truths. Most of these base beliefs do not change, but they are so abstract and detached from everyday opinions that they do not matter at the granularity I’m considering here, whether in writing or elsewhere. For example, it is normal for me to believe in a God, then renounce it, and later develop a second passion for a God, the same or another.

I think of someone who changes their mind repeatedly as being weak, in the sense of being unreliable or flaky. At the same time, I appreciate the flexibility and self-doubt of someone. Both the flakiness and the flexibility make sense to that person in that situation, given their perspective at that exact moment.

When someone changes their mind, one factor that leads them to do that (among others) is their own prior opinion. What happens is that opinion got inscribed in time, the person moved on. This way of looking at things is opposite to what I wrote in the opening above -- “writing binds me irreversibly to certain beliefs” -- proving my point at least in this case.

One book I found very instructive on the topic of time is “The Order of Time” by C. Rovelli. ↩︎

Comments ()