Notes on individual psychology

At the beginning of 2024 I went down the rabbit hole of individual psychology. It has proven to be a very fruitful source of insights and direction for personal growth. Alfred Adler created this sub-field of psychology around the 1910s. He is one of three early fathers of psychology, alongside Freud and Jung.

My notes below are primarily inspired from the book “The Courage to be Disliked” of Ichiro Kishimi & Fumitake Koga. I also took inspiration on Adlerian thought from various online articles, most of which I quote at the bottom.

Adlerian thought, in one paragraph

Adler believes all our actions have a goal. This goal is the most important element under our control, in how we act and where we arrive in life. Being deliberate about one's goal is the best way to find peace or fulfillment.

The field is called individual psychology because of this emphasis on goals – everything reduces to the individual and his or her actions.

Key concepts

Above is the simplest way I have found to explain Adlerian psychology. It is a set of concepts that is very dense, however. So here are some subtler points that stood out for me..

Focus on Goal

Adlerian psychology is very pragmatic: Everything we do, we do it because we have a certain goal. Moreover, the goal is sometimes implicit, unknown to our conscious mind. Other times, it is explicit, and we are pursuing the goal with deliberate focus.

Even more interesting, on the surface our goal may look undesirable, for example when someone harms themselves. In such a case, the likely underlying goal is getting attention. Hurting oneself is a means, not a goal. Whether implicit or explicit, we always have a goal and are pursuing certain intentions.

“Adlerian teleology does not turn a blind eye to the goal that the child is hiding. That is to say, the goal of revenge on the parents. If he becomes a delinquent, stops going to school, cuts his wrists, or things like that, the parents will be upset. They’ll panic and worry themselves sick over him. It is in the knowledge that this will happen that the child engages in problem behavior. So that the current goal (revenge on the parents) can be realized, not because he is motivated by past causes (home environment).”

(Kishimi & Koga, CD)

I used to think there’s intuitively two levels to everyone’s behavior: subconscious, and conscious. The first always overrules the second. Influenced by reading this book, it seems more accurate to name the first level something like subconscious goals – a mix of emotion, personality, circumstances past & present. Sometimes, these goals bubble to the surface of consciousness, and when they do, there seem to be three levels we can distinguish: subconscious goals, conscious goals, conscious actions.

“At some stage in your life, you chose “being unhappy.” It is not because you were born into unhappy circumstances or ended up in an unhappy situation. It’s that you judged “being unhappy” to be good for you.”

(Kishimi & Koga, CD)

This part of the theory is a hard pill to swallow. Probably the last thing a hurting person wants to hear is that they chose to be in a sorry state. It depends a lot on how this message is conveyed to the person, however, and the meaning they construct from that difficult experience. It may well be that their response is constructive, or they feel motivated if we frame the situation as, It's actually under your control. In any case, Adlerian perspective would posit that we determine our life more than we think, through the meaning we give to our experiences and the goals we have exhibited in our behavior. What matters is not what happens to you, but how you respond. I would agree with this.

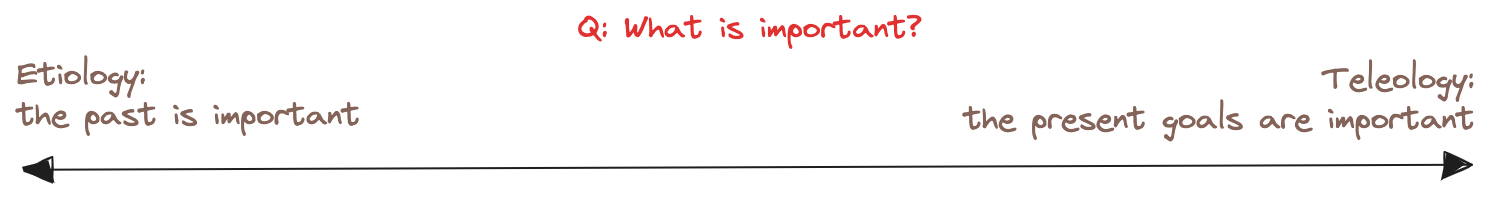

You become what you intend to become

Suppose we use Freud’s idea of focusing on trauma and past to interpret reality and take decisions. This is an etiological approach, where we tend to over-index on those elements of past in our life. Our goal (which is probably implicit) in doing so is reliving and integrating those prior experiences. Adler would probably say this is a distraction, that this doctrine of focus on the past is unconstructive to a well-lived life. That we should, instead, focus on what we want to achieve. Maybe to be a great partner to someone? Or maybe start a venture? Or start a family? This is a teleological approach, i.e., starting with the end in mind.

This is the same idea as before: Focus on your goal. To complement that, here I am describing a sketch of a mental model.

Going further, Adler denies that traumas are important in and of themselves. Whereas other psychologists obsessed about traumas, Adler thinks we ourselves assign meaning to experiences or episodes of our life. We choose to let them affect us (or not) in certain ways. Put differently, trauma is real, but we determine what meaning it carries. What is a delight for someone may be hellish for someone else, and vice versa, and this is under our control.

[Adler] is not saying that the experience of a horrible calamity or abuse during childhood or other such incidents have no influence on forming a personality; their influences are strong. But the important thing is that nothing is actually determined by those influences. We determine our own lives according to the meaning we give to those past experiences. Your life is not something that someone gives you, but something you choose yourself, and you are the one who decides how you live.

(Kishimi & Koga, CD)

I notice an overlap between individual psychology and existential philosophy. The former likely influenced the latter. Both of them emphasize that we are each free to assign meaning to our experiences and to choose how to conduct ourselves. The overlap becomes even more evident in the following point about freedom.

Freedom

The book offers a very practical definition of freedom: Being disliked by other people. Or to phrase it more intuitively, if a person is disliked, that is the proof that the person is exercising their individual freedom. It takes a certain dose of courage to recognize this freedom exists, and courage to act on it, even if means disagreeing or diverging from others. (Emphasizing here courage, which I'll give more attention in a sec.) For example, thinking in first principles, making unpopular claims or life decisions, going against trends.

Courage

Why courage? The book is about self-growth, so why isn’t it about “overcoming past traumas” or “integrating our shadow in our character” (Jungian) or “learning to love every moment as necessary” (Nietzsche) or “recognizing identification with thought and surrendering to experience” (various mindfulness schools of thought)?

From what I understand, the answer to that question goes back to teleology. Courage is the psychological state in which someone faces the present and future with clarity, unblemished by influences from the past that do not serve us. It is the willingness to put aside whatever happened and press onward. This framing of courage is my favorite takeaway overall from individual psychology. It makes sense that Kishimi & Koga's book would be named after this insight.

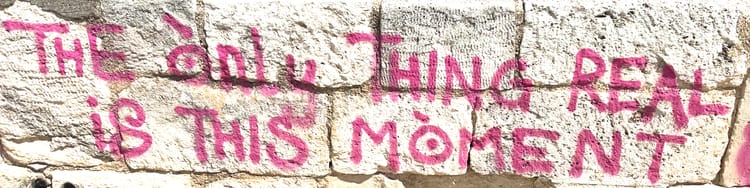

This insight is also behind the quote in the photo at the top of this article, "I think you don't have to sign everything." The quote about signing is from Arnold Zweig, an influential literary figure of East Germany. I snapped the photo in a museum in Berlin. The quote is relevant because I understand it to reflects Zweig's courage to think for himself when surrounded by pressure in the society around him to declare certain things as black or white. Some more details here or here.

More on Courage

“If I stay in my room all the time, without ever going out, my parents will worry. I can get all of my parents’ attention focused on me. They’ll be extremely careful around me and always handle me with kid gloves. On the other hand, if I take even one step out of the house, I’ll just become part of a faceless mass whom no one pays attention to. I’ll be surrounded by people I don’t know and just end up average, or less than average.”

(Kishimi & Koga, CD)

This is a difficult quote to wrestle with. How does someone feel like they have worth? How does someone get the courage?

When I was in graduate school, and also as part of my work in Informal, I often encountered situations where I was silently enduring a problem, hesitant or afraid to bring it up with my advisor, colleagues, or manager.

A common situation was where I was insecure about an initiative or idea I had. Is this idea worth its salt? Such went my inner monologue. Is this improvement worth even discussing at the weekly stand-up? Is my CEO going to think I'm investing too much time in this rabbit hole? And so on. I would hesitate to bring up the topic. Maybe it was often a trivial issue, not worth any effort. But what I found over and over again was different. Summoning the courage to discuss the idea paid off every time. Even if it was not immediately valuable, my colleagues would dismiss it with encouraging words, and the discussion that I sparked proved to be productive, or least entertaining or insightful.

Only the most destructive environments punish people for asking input on something they tried on their own. Fortunately, I did not experience this. Though I'm sure my inner critic is being protective for good reasons, those reasons are mostly obsolete.

Courage in these kind of situations always worked positively. It is not an example of courage to save a soldier buddy in the WWI eastern front trenches, nor to make a very difficult choice in adverse times. So we could argue the example above is a first world problem, but the point still stands. Also interestingly, there is a link here with what I wrote earlier about Stewards and Pilgrims. Namely, the role of stewards in an organization has a positive side effect of stirring up courage in the pilgrim.

Now back to Adler.

Maybe a child doesn’t feel like doing their homework. Or maybe a friend is postponing a difficult choice in their life. Adler would say we should always encourage others arounds us, especially if they might have lost the courage to face their task or goal. As a more broad proposal, Adler goes quite far with the impact that courage can have on anyone's life. Again, he says it takes courage to choose to be happy, because it means changing our lifestyle, trying different mindsets, iterating on different behaviors, and it can be painful to separate with the past.

“I have a young friend who dreams of becoming a novelist, but he never seems to be able to complete his work. According to him, his job keeps him too busy, and he can never find enough time to write novels, and that’s why he can’t complete work and enter it for writing awards. But is that the real reason? No! It’s actually that he wants to leave the possibility of “I can do it if I try” open, by not committing to anything. He doesn’t want to expose his work to criticism, and he certainly doesn’t want to face the reality that he might produce an inferior piece of writing and face rejection. He wants to live inside that realm of possibilities, where he can say that he could do it if he only had the time, or that he could write if he just had the proper environment, and that he really does have the talent for it. In another five or ten years, he will probably start using other excuses like “I’m not young anymore” or “I’ve got a family to think about now.””

(Kishimi & Koga, CD)

This is another difficult paragraph. It is very similar to the kind of mentality that Pressfield proposes in The War of Art.

Horizontal relationships

The last concept I'll discuss.

This idea is even more idealistic than prior ones, but is also very practical. As opposed to a vertical relationship, a horizontal relationship is one between equals. A good example is with kids. It's easy to grasp what a vertical relationship looks like when raising a child, because we offer constantly our judgements of what is good and bad. We do it both applied to the child's behavior and for external events also. A horizontal relationship would lack such judgements.

One must not praise. And one must not rebuke, either. All words that are used to judge other people are words that come out of vertical relationships, and we need to build horizontal relationships. And it is only when one is able to feel that one is of use to someone that one can have a true awareness of one’s worth.

(Kishimi & Koga, CD)

Something that is relevant to me is that judgements often emerge from the depths of our instinctual mind, as a first level of sense making. They may be a knee jerk application of biases or prejudices. From this perspective, it's easy to get the appeal of horizontal relationships and see how they're not a purely idealistic theory.

If one is building horizontal relationships, there will be words of more straightforward gratitude and respect and joy.

(Kishimi & Koga, CD)

This is compassion. Many modern books on self-help and personal development will likely touch on the mindset of releasing judgements, or "not giving a f*ck". It's a low hanging fruit.

Adler’s theory is similar to the humanistic psychology of Abraham Maslow, who acknowledged Adler’s influence on his own theories. Both maintain that the individual human being is the best determinant of his or her own needs, desires, interests, and growth.

(Wikipedia)

I left out one banger, namely, self-acceptance. I found that was the point where the book departs more clearly from psychology and enters the spirituality domain, crossing also over into Zen. I found it very difficult to write anything authentic on that point. Hopefully, in a future essay.

Notes & sources:

- CD: “The Courage to be Disliked” of Ichiro Kishimi & Fumitake Koga

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Individual_psychology

- Libretexts.org, Mark D. Kelland, 4.2: Brief Biography of Alfred Adler

- 20 Pros and Cons of Adlerian Theory

- Youtube, Academy of Ideas, The Psychology of Alfred Adler: Superiority, Inferiority, and Courage

Comments ()