Pilgrims and their Stewards

There is an analogy I stumbled upon recently. I found it insightful because it brings together two paths I’m treading on at the moment.

1. Enter the pilgrim

I think everyone is a pilgrim.

Everyone is a pilgrim in the sense that life is a constant process of discovery and learning. Simply put, there are always questions unanswered that call upon us, or we always have some objectives we are wayfaring towards.

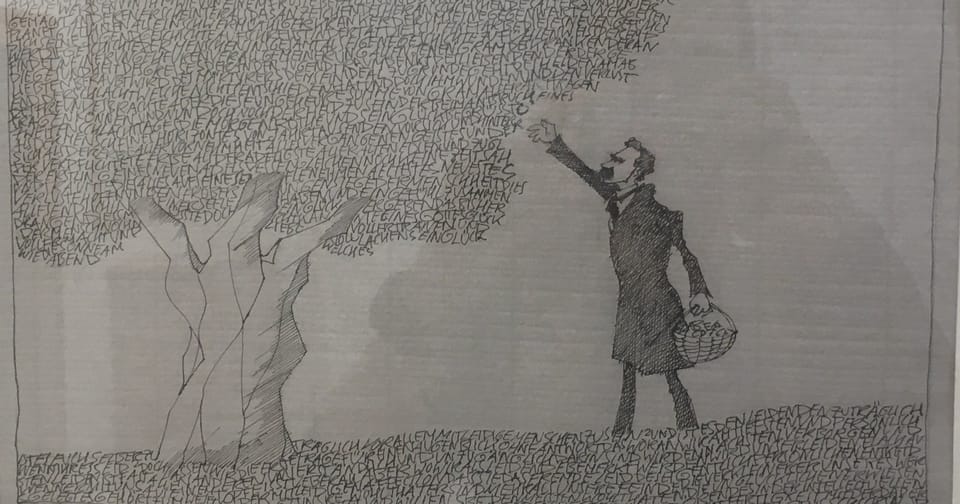

A pilgrim is not religious in a conventional view of religion. But while we’re here, let’s state this out loud: Everyone has a religion. The most strikingly free spirit I ever encountered is Nietzsche, and he himself admits having a dogmatic belief -- namely, with respect to truth and its value.

There are several helpful attitudes that I try to nurture in myself, and one of them is that I will for ever try to be a pilgrim. I find it helpful to think and act in line with this attitude because it reduces immensely the pressure that I naturally put on myself, the pressure that I should know this or should do that or be better than him or her. That pressure certainly has some positive sides, but it can be quite unjust, almost tyrannical, so I don’t want to leave it unchecked. I found that one very good way of checking it is through the mentality of a pilgrim.

A concrete example where this attitude is directly helpful would be in the context of receiving an unflattering comment from someone. A pilgrim would thirst for that and welcome it. In my default state, on the contrary, I would probably resist and close myself to such feedback, as constructive as it may be.

There is one aspect of being a pilgrim that I find very difficult to grasp, however. It’s in fact a central element of pilgrimage, but nonetheless quite slippery, and has to do with the relation between myself and my lessons as I thread along: It seems to be fundamentally useless if a lesson arrives at me directly, say from a mentor. Let’s take, for a example, a very common-sense lesson such as this one from a stoic:

Man is disturbed not by things, but by the views he takes of them.

-- Epictetus

Suppose Epictetus was helping me on my pilgrimage, and among the few bits that he would impart to me there would be this one. Suppose I can grasp what Epictetus means, the lesson here being that if I’d like to become less disturbed in general, then it would be beneficial to remember that there is nothing inherent in my surroundings that disturb be, and rather it’s my own mental acrobatics that bring disturbance. Simple enough!

Again -- suppose I understand what Epictetus means.

Even if I do, the problem is that shortly after understanding him, I would probably ignore his lesson, and let myself be disturbed by something in the course of the day or, at the very least, distracted. The problem is I will not have learned anything directly from him.

Why is it most useful to learn indirectly, or from my own mistakes -- as opposed to absorbing Epictetus wisdom directly? I may eventually learn from his wisdom, but only after years and years of digesting the quote above, after one or multiple iterations witnessing in practice the futility of letting myself get disturbed by various views of things.

There are many reasons why my experience must be this way.

Intuitively, I have a certain speed of adapting and learning. To be more specific, I have made heavy investments in my current practices. Consequently there are inherent cognitive barriers that prevent me from simply abandoning these practices off the bat. My current habits make me who I am, they are wired in and rewiring takes time.

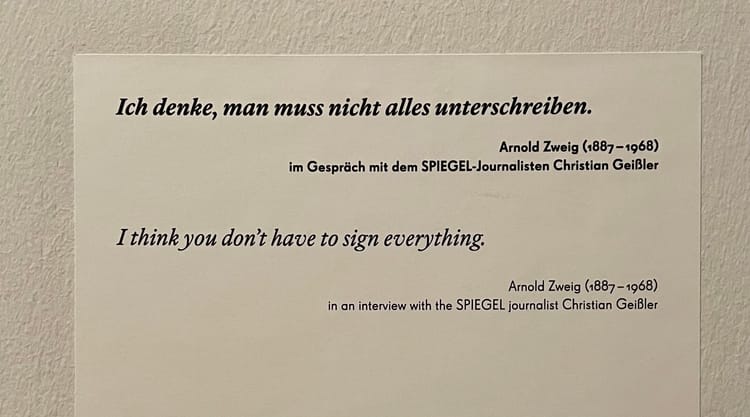

Yet I think most important reason is the following: There is no reason why Epictetus should be correct in the above quote. Phrased as a question: Why should I learn directly from him? The world is constantly changing and there may well come a time when Epictetus’ assertion is false, that is, when man will no longer be disturbed by the views he takes of things. Because of this, I have to re-asses the truth and value of his lesson before it can become actively valuable to me, before it becomes me. And it’s quite fortunate humans are like that. Imagine, as a thought experiment, what it would be like otherwise -- what would it be like if our nature allowed us to do significant changes to our character based on the mere sayings of someone else?

Mistakes must be made. Simplicity, in my behavior and approach to life, seems to depend on a great deal of individual search and trial and error. This aspect of individuality of a pilgrim’s journey is what I find to be most central and tricky.

2. Enter the steward

Since I am a pilgrim of life in general, I am also a pilgrim at my work. The context shrinks, becoming more specific, but the dynamic remains unchanged.

Being a pilgrim in the context of an organization means, roughly speaking, that the organization is the world, and as the world keeps changing and adapting in complex ways, so I keep striving to find a place to contribute in a way that is most appropriate for my skills and interests in that world.

A steward resembles a coach. This is a person who helps guide the worker-pilgrim in planning for the future of their career. The important part is this: Just like I am a full individual in the world, so am I a full individual in the organization I belong to. This means a steward’s role is not that of imparting lessons and managing my career. Instead, it is rather about encouraging me to find my way and helping me clarify it and walk it.

I first learned about stewards from my colleagues, who suggested reading an article called “The Collaborative Web”. A simple and straightforward formulation of what a steward is comes from that article, as follows:

stewards are measured best by asking how well they are able to “be the mirror” [..], that is, to reflect back to an individual what they have already claimed is important to them, and to ask the question about how well their current actions are helping them to achieve that result.

The relation between a worker-pilgrim and their steward is akin to that between any person and their guiding voice -- whether that voice is wholly internal, a pastor, a therapist, Epictetus or other dead philosophers, a father or mother, a coach, and so on. The relation is centered on trust, and it is always up to the pilgrim to look in the mirror with honesty. The pilgrim always gets to do the first move. The mirror cannot teach anything, but it can unveil angles that are concealed to the naked eye, reveal aspects that are hidden from plain sight. And so the pilgrim can learn.

Just like I cannot build on the life experience of Epictetus directly, I cannot learn from stewards directly either. This is probably one of the reasons why the relation steward-to-learner is explicitly not formulated in terms of learning, but in terms of supporting reflection.

The learning and development we undergo in the context of a career is no different than our maturing in the broader context of life. At this level, there is no reason why the two trails should be separate. As obvious as this sounds, it wasn’t clear to me until I discovered stewards, their role, and saw that on a basic level there is no division between career and personal.

The amount of moral development I can undertake has clear limits. It seems bounded by my capacity to asses the truthfulness of novel ideas in practice. To test these ideas, to practice them, to speak them, attack and defend them, and even let them take a life of their own. To own their consequences and toss them away if they prove untrue. The testing out part seems to be the defining element of pilgrimage, and the most help a pilgrim can get is a trusty, heartening mirror. I like that.

I’ll wrap up with a pithy quote from one of my favorite books.

What is to be learned is too elusively simple to be grasped without struggle, surrender, and experiencing of how it is.

Sheldon B. Kopp, “If You Meet the Buddha on the Road, Kill Him”

McKinney, Laura, and Jef Bell. “The collaborative web: Building a divergent organizational model for research and development, based on 21st century notions of employee engagement.” In Proceedings of PICMET’14 Conference: Portland International Center for Management of Engineering and Technology; Infrastructure and Service Integration, pp. 7-17. IEEE, 2014.

Comments ()